With the Women’s Classical Committee’s 50th Wikipedia editing event taking place today(!) now seemed like a good time to crunch some numbers and see how things are going.

Usually, I’d try to do this in December but the Denelezh gender gap analysis tool I’ve used in the past and which does a lot of the heavy lifting was down in December. It’s back online now, but the most recent data it has is from September 2020, and has been replaced by WDCM: Biases. It seems to run in a similar way by querying Wikidata around gender, occupation, and different wiki projects but seems to have fewer ways to explore the data. For example, I can find information on gender gap by profession of wiki project, but not how the two intersect. So I’ll be trying running a few manual queries to showcase the gender gap and recording the results here. As the queries are working from the live data, the figures will eventually drift what what is written in this blog.

Headline numbers

| Female | % female | Male | Other genders | Total | |

| Classical scholars | 454 | 17.7% | 2,112 | 0 | 2,556 |

| All of English Wikipedia | 347,033 | 19.0% | 1,479,272 | 1,447 | 1,827,752 |

So as of 28 July 2021, the English Wikipedia has 454 biographies of female classicists, which is 17.7% of the total. This is progress from December 2019 when the 384 biographies of female classicists made contributed 16.3% over the overall biographies of classicists on the English Wikipedia and the proportion continues to climb.

It’s worth noting that Wikidata can accommodate information on different genders – it’s not just binary – but verifying that can be tricky. For modern classicists, this information may be highly sensitive and for historical classicists many of the sources won’t address the issue. Hence, there may be a gap as a result.

| Date | Female | % female | Male | No data | Total |

| Jan 2017 | 36 | 5.3% | 645 | 0 | 681 |

| Dec 2017 | 176 | 10.0% | 1,586 | 3 | 1,765 |

| Dec 2018 | 268 | 12.8% | 1,820 | 2,088 | |

| Dec 2019 | 384 | 16.3% | 1,975 | 0 | 2,359 |

| Sep 2020 | 424 | 17.1% | 2,053 | 0 | 2,477 |

| Jul 2021 | 454 | 17.7% | 2,112 | 2,566 |

Change since December 2019

The last 19 months has been a time unlike any other we’ve lived through as for most of that time we’ve had to deal with a pandemic. The Women’s Classical Committee already ran monthly online editing events, so were well placed to continue those. The potential difficulty is that Wikipedia editing is largely extra-curricula, and when you’re dealing with a crisis non-essential activities can naturally contract.

#WCCwiki persevered and continued to make a different which is all the more important give how much academics have had to deal with due to the shift to online teaching, and not to mention the general precarcity of academia.

| Female | % female | Male | Total | |

| English Wikipedia | 70 | 33.8% | 137 | 207 |

By comparison, in the whole of 2019 there were 271 new biographies of classicists on the English Wikipedia, and 42.8% were about women. That was an excellent result, and the progress made in 2020 and 2021 represents the resilience of #WCCwiki.

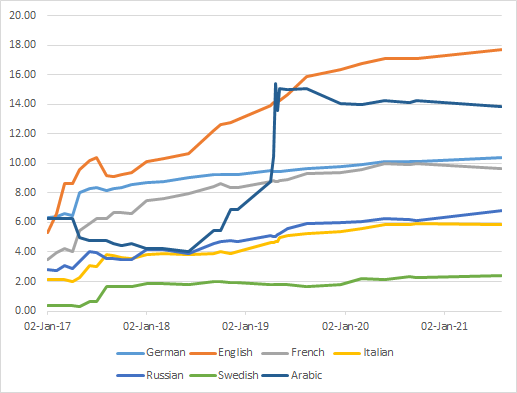

Other languages

I miss the Denelezh tool. It made this bit so easy. Where it gives you an overview by Wikipedia language, I have to run a query for each. I’ll focus on the languages which had more than 450 biographies of classicists in December 2019. Apologies for the monster table below.

| Dec-19 | Dec-19 | Dec-19 | Dec-19 | Jul-21 | Jul-21 | Jul-21 | Jul-21 | Change | Change | Change | Change | |

| Wikipedia | Female | % female | Male | Total | Female | % female | Male | Total | Female | % female | Male | Total |

| German | 322 | 10% | 2973 | 3295 | 376 | 10% | 3238 | 3614 | 54 | 17% | 265 | 319 |

| English | 384 | 16% | 1975 | 2359 | 454 | 18% | 2112 | 2566 | 70 | 34% | 137 | 207 |

| French | 92 | 9% | 885 | 977 | 106 | 10% | 994 | 1100 | 14 | 11% | 109 | 123 |

| Italian | 42 | 5% | 737 | 779 | 53 | 6% | 854 | 907 | 11 | 9% | 117 | 128 |

| Russian | 42 | 6% | 658 | 700 | 54 | 7% | 735 | 789 | 12 | 13% | 77 | 89 |

| Swedish | 10 | 2% | 536 | 546 | 14 | 2% | 561 | 575 | 4 | 14% | 25 | 29 |

| Arabic | 68 | 14% | 423 | 491 | 74 | 14% | 459 | 533 | 6 | 14% | 36 | 42 |

The important bit is how the change in the English Wikipedia compares to other languages. 34% of the new articles about classicists on the English Wikipedia were about women. This is twice that of the German Wikipedia, and triple that of French. It shows very clearly what that without the efforts of the Women’s Classical Committee new Wikipedia biographies would have a much stronger male bias.

The field of classics on Wikipedia was in a bad state at the start of 2017. While it has been gradually improving since, it still languishes behind the overall gender gap on Wikipedia. The English Wikipedia’s proportion of biographies about women has outpaced any other Wikipedia. Arabic Wikipedia had a remarkable 2019, but at the other end of the scale the Swedish Wikipedia has a lot of ground to cover. Worryingly, Italian and French appear to have a downward trend.

Archaeology

In 2018 and 2019 I included some figures on classical archaeologists, and for some effort of completeness here they are with an update:

| Language Wikipedia | Female | % female | Male | Total |

| English, 14 Dec 2018 | 37 | 19.2% | 156 | 193 |

| English, 6 Dec 2019 | 85 | 29.1% | 207 | 292 |

| English, 28 Jul 2021 | 109 | 32.3% | 228 | 337 |

In 2019 there was a roughly even split between the number of new biographies of men and women who are classical archaeologists, and since December 2019 the new biographies of women have slightly outnumbered those of men. It was already tracking above classical scholars as a whole, so this is very encouraging. As it’s a small group, progress can be much quicker.

Though it’s not specifically about classics I’m happy that the number of medieval archaeologists with biographies has increased from 4 in December 2019 (1 male, 3 female) to 23 in July 2021 (9 male, 14 female), but at least part of this must be due to the underlying data being improved rather than brand new articles.

Conclusion

The Women’s Classical Committee have been working together to improve Wikipedia for several years. They are an outstanding example of what can be accomplished, and longevity. Way back in 2016, the data I had indicated that 7% of the English Wikipedia’s biographies of classical scholars were about women, and in absolute terms that meant fewer than articles. The data above makes it clear that the intervention of #WCCwiki has enriched Wikipedia.

This only scratches the surface as it doesn’t take quality into account. As well as creating new pages, #WCCwiki revisit pages and update them, quantity and quality going hand-in-hand.